Local Policy Tools for Protecting Freshwater Resources

New Jersey’s freshwater wetlands, lakes, and streams are a resource valued at approximately $10.1 billion per year for their role in providing clean drinking water, regulating floods, and supporting habitat and outdoor recreation1. Yet, despite protective regulations at the state level, the quality of these important resources is threatened by the slow creep of many small but collectively significant disturbances.

Filling streams and wetlands for development is generally prohibited by state law. However, there are a number of special permits that the state may issue to allow certain types of disturbances adjacent to or within streams and wetlands, and unfortunately many of these are quite common.

Since the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection preempts local authority in wetland matters, planning and zoning boards cannot deny development applications on the basis of wetland impacts alone. However, with a bit of foresight, there are a number of ways municipalities can better plan for new development and minimize impacts to wetlands, lakes, streams, and other natural resources.

Local Policy Tools

An Environmental Resources Inventory (ERI), also known as a Natural Resources Inventory (NRI), is a narrative document that often includes maps, data, and photos characterizing the location, quality, and importance of existing natural resources within the community. ERIs are typically developed and managed by the Environmental Commission, and can be an important reference for planning boards during the site plan review process.

In order to be most useful as a tool for protecting water resources, ERIs should include as much detail as possible about the function and quality of different wetland regions and water bodies. For example, rather than making generic statements about the value of wetlands, the ERI should seek to assign specific values to wetland patches and stream reaches based on connectivity, location, and observed habitat. Local conservation organizations can be helpful in providing data on recreation, habitat, and conservation value. Water resources authorities can provide information on where drinking water comes from, and which regions are most important to protecting water quality. Engineering and public works departments can share information on recurrent flooding issues. All of this information can help characterize the importance of specific areas in terms of services provided to local residents.

Master plans outline a vision for the character, economy, and appearance of a municipality, and enable the creation of land use ordinances to ensure consistency with this vision. As such, the master plan is a municipality’s best tool for shaping development patterns in a way that serves the needs and values of the community. By designating certain areas for certain types and densities of development, municipalities can help preserve undeveloped natural areas, promote redevelopment, and encourage density in the least sensitive areas that are best served by existing infrastructure. This document is very useful in articulating a vision to developers, who can then plan investments accordingly.

Land Use

The Land Use Element of a master plan is a required section that designates specific regions to be used for commercial, industrial, residential, and open space uses. It also determines specific uses and densities related to the planned character of each region.

There are many ways the Land Use Element can be used to protect water resources. For example, when designating certain regions for commercial or industrial land uses, planning boards are able to direct development toward those areas with limited water resources value, while promoting lower-impact development and open space in areas with wetlands, streams, forests, and sensitive habitats. For example, limits to residential density (such as minimum lot sizes) can help developer’s avoid certain impacts by ensuring a higher level of flexibility when it comes to siting the building footprint (however, these limits can also encourage the development of very large lawns, which are environmentally problematic for other reasons). The Land Use Element can also incorporate set-asides for conservation and recreation, and promote the use of green infrastructure where appropriate.

Conservation, Recreation, and Utilities

Additional optional elements may include conservation, recreation, or utility sections that can be used to limit wetland and stream-side development based on expected uses for conservation, recreation, or water supply. By articulating wetland protection needs in these sections, municipalities can create pathways for fundraising and conservation acquisition, and further link place-based values with actual ecosystem services.

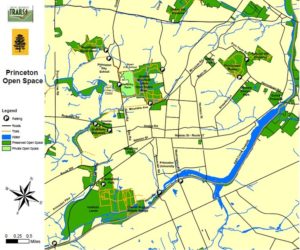

Acquisition of land, easements, or development rights can be a very effective, if costly, means of preserving wetlands and stream corridors. This strategy is most effective in regions served by an active land trust, or where the county or municipality has already established an open space trust fund. Effective land preservation is often the result of coordination between local government, landowners, and nonprofit groups that come together to pool resources to preserve a valuable piece of property.

Understanding and articulating how the property fits into the broader ecological and social context is an important step in building support for land acquisition projects. The New Jersey Conservation Blueprint is a helpful mapping tool that prioritizes lands for preservation based on estimated value in terms of water quality, climate resilience, biodiversity, community green space, and agricultural heritage.

In New Jersey, municipal planning, zoning, and land use boards exercise review power over land development applications, and may choose to review or deny applications within the confines of New Jersey Municipal Land Use Law. Members of the boards are not elected but rather appointed by government officials. Their process of review and approval includes a public hearing, with opportunities for public input by residents and stakeholders. These hearings provide an excellent opportunity for concerned members of the public to ask questions and voice their concerns or support for development projects. In order to be most effective, however, it is important to understand the issues at stake locally as well as the governing body’s powers in approving or denying the application.

To learn more, refer to the Monmouth County Audubon Society’s Ten Steps for Opposing Bad Development, or the Watershed Institute’s The Power of Public Participation: Get Involved to Protect the Place You Call Home.

A stream corridor is composed of several essential elements including the stream channel itself, floodplains, and forests. Where stream corridors are maintained in their natural condition with minimum disturbance, they are instrumental in removing sediment, nutrients, and pollutants by providing opportunities for filtration, absorption and decomposition by slowing stormwater velocity, which aids in allowing stormwater to be absorbed in the soil and taken up by vegetation. They also reduce stream bank erosion, displace potential sources of non-point source pollution from the water’s edge, and prevent flood-related damage and associated costs to surrounding communities.

A stream corridor ordinance can be used to require additional protections for local streams and their adjacent wetlands beyond what is required by the State.

The following additional measures can help fill the gaps in State regulations, and ensure that protections are maintained locally in the event of State rollbacks:- Establish a minimum stream buffer width of 150 feet. This area may often include important riparian wetlands.

- Include all surface water bodies in the ordinance, including ponds and lakes – which may have significant adjacent wetland resources.

- Reduce the amount of building allowable in stream corridors that are not part of a Flood Hazard Areas or Special Flood Hazard Areas.

- Stream corridors are important to help prevent flooding along the entire length of a waterway, not just in areas already prone to flooding.

After draining or filling, stormwater inundation or diversion (that is, changing the natural drainage patterns to or from a wetland or stream) are two of the major causes of freshwater degradation. While towns may not explicitly regulate wetlands, they are required to enact ordinances to regulate what types of development trigger stormwater management rules, and how and to what extent stormwater is treated before it is released back to the drainage network of ditches, pipes, wetlands, and streams. Most towns simply incorporate default state-level rules for stormwater management, however, added protections can be gained with a few key changes:

- Lowering the threshold for “major development” from one acre to half an acre.

- Including redevelopment, even if no new impervious surface has been added.

- Creating a separate category for “minor development” which incorporates pre-approved residential scale treatment measures such as reuse cisterns and rain gardens.

- Increasing pollution reduction requirements in watersheds where a Total maximum Daily Load (TMDL) has been established for certain pollutants.

- Increasing incentives/requirements for the use of porous pavement.

Additional Resources

You can learn more about tools for protecting wetlands in your community from the following resources:

References

1Valuing New Jersey’s Natural Capital: An Assessment of the Economic Value of the State’s Natural Resources, Page 17 (April 2007).