Staff and scientists steered The Watershed Institute’s speedboat into Rosedale Lake and dropped the first of 20 floating wetlands into the waters in an innovative approach to halt toxic algae blooms and improve water quality.

Instead of using chemicals, these large floating wetlands are planted with fast-growing grasses, swamp milkweed, and cardinal flowers. These hardy, long-rooted plants will soak up nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients that stimulate the growth of blue-green algae, posing health threats for people, pets, and other animals.

For several summers, many New Jersey waterways — including Rosedale Lake — have been closed to swimming, fishing, and other recreation because of the rise of harmful algal blooms (HABs) caused by excessive pesticides, fertilizers, and other pollutants flowing into the water from tributaries and nearby lands. One pound of phosphorous can stimulate the growth of 1,100 pounds of algae in a lake or pond.

For several summers, many New Jersey waterways — including Rosedale Lake — have been closed to swimming, fishing, and other recreation because of the rise of harmful algal blooms (HABs) caused by excessive pesticides, fertilizers, and other pollutants flowing into the water from tributaries and nearby lands. One pound of phosphorous can stimulate the growth of 1,100 pounds of algae in a lake or pond.

Over two days (May 20 & 21), about 25 Watershed and Trout Unlimited volunteers planted and deployed all 20 floating wetlands. The Watershed was contracted by Mercer County to help combat the HABs using funds from the federal Clean Water Act.

“The purpose of the floating wetlands is to reduce the nutrients that drain into the lake from polluted stormwater. The nutrients come from fertilizers from grassy areas, nearby lawns, and animal waste,” said Steve Tuorto, Ph.D., Director of Science at the Watershed.

Watershed staff will monitor these 50-square-foot wetlands for two years to determine their efficacy. Additionally, county officials will add lake aeration devices and barley bales along the shoreline to absorb polluted stormwater runoff coming from nearby lands and upstream tributaries that drain into Rosedale Lake.

Watershed staff will monitor these 50-square-foot wetlands for two years to determine their efficacy. Additionally, county officials will add lake aeration devices and barley bales along the shoreline to absorb polluted stormwater runoff coming from nearby lands and upstream tributaries that drain into Rosedale Lake.

Several years ago, the Watershed installed seven similar wetlands as a pilot project at an East Windsor senior residential community, and they appear to be effective at absorbing nutrients. Tuorto said those experiences helped Watershed staff select the best plants to use on Rosedale Lake’s floating wetlands, which he and others built using marine foam, jute, soil materials, and filter floss material made from recycled plastic.

“We’re simplifying the process and are sticking with plants we know will survive and be efficient and create strong systems,” he said. “While we haven’t specified how long the floating wetlands will remain in Rosedale Lake, we will inspect them for several years and make sure the plants survive and aren’t damaged by wildlife.”

“We’re simplifying the process and are sticking with plants we know will survive and be efficient and create strong systems,” he said. “While we haven’t specified how long the floating wetlands will remain in Rosedale Lake, we will inspect them for several years and make sure the plants survive and aren’t damaged by wildlife.”

These toxic algae blooms are most commonly caused by phytoplankton known as cyanobacteria that use sunlight to create food. Excess, dense blooms – sometimes resembling pea soup – develop when certain cyanobacteria encounter ideal conditions including sunlight, warm temperatures, high nutrients, and calm water. According to the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the warmer days caused by climate change may result in more HABs.

On May 23, volunteers with the Watershed’s StreamWatch bacterial action team will begin conducting weekly lake assessments at about 30 locations in New Jersey, including Rosedale Lake. These volunteers are focused on multiple types of bacteria – conducting visual assessments for cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms and collecting water samples to be analyzed for E. coli and total coliform bacteria. Data will show up in real-time at thewatershed.org/streamwatch so check back on your favorite waterbody every week.

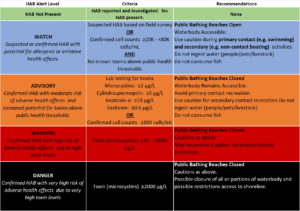

Last year, the state Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) has created a color-coded warning system for ranking the HABs in waterways and for alerting the public.

Rosedale Lake was not alone in having restrictions placed on lake activities. There was also a widely-reported harmful algal bloom (HAB) advisory for Lake Hopatcong, the state’s largest freshwater body, in Morris and Sussex counties, and Mountain Lake in Warren County. In 2017 and 2018, there were a total of 64 HAB advisories. You can review a listing of all of the 2019 HABs on NJDEP’s website. Explore NJDEP’s website to learn more about HABs.

Rosedale Lake was not alone in having restrictions placed on lake activities. There was also a widely-reported harmful algal bloom (HAB) advisory for Lake Hopatcong, the state’s largest freshwater body, in Morris and Sussex counties, and Mountain Lake in Warren County. In 2017 and 2018, there were a total of 64 HAB advisories. You can review a listing of all of the 2019 HABs on NJDEP’s website. Explore NJDEP’s website to learn more about HABs.

Community scientists will help monitor HABs in their areas. Using a few dozen fluorometers from EPA Region 2, the New Jersey Watershed Watch Network and the state’s Bureau of Freshwater and Biological Monitoring will distribute phycocyanin meters to community water monitoring groups throughout the state. The network is coordinated by the Watershed’s Assistant Director of Science Erin Stretz.

Phycocyanin is a blue photopigment similar to chlorophyll and its levels can be correlated with approximate cyanobacterial cell counts. Putting this simple tool in community scientists’ hands will help quantify the extent and severity of algal blooms, while allowing experts to quickly share this information with the public.