When the roads get slippery, our streams get salty.

As local public works departments spread rock salt or pre-emptively wet the roads with brine before major storms, these salts wash into our waterways.

The salty water ends up in our household drinking water because private wells and public water utilities draw water from local streams, reservoirs, and aquifers. Road salt often soaks into our groundwater, which directly introduces excess sodium into drinking water and poses a health risk, especially to people on low-sodium diets.

De-icing and road wetting chemicals — sodium chloride, calcium chloride, magnesium chloride, calcium magnesium acetate, and potassium acetate — end up degrading the water quality of local streams, harming the microscopic critters who live in the water and negatively impacting wildlife.

De-icing and road wetting chemicals — sodium chloride, calcium chloride, magnesium chloride, calcium magnesium acetate, and potassium acetate — end up degrading the water quality of local streams, harming the microscopic critters who live in the water and negatively impacting wildlife.

Experts say overuse of rock salt and brine is common because these are relatively cheap materials to apply in the name of public safety. Municipalities have begun a practice of spraying brine before storms or, depending on the temperature, during storms to augment the use of rock salt, which often bounces off the road’s hard surface and ends up along the shoulders.

Even after the snow and ice melt away, the salt residue remains on the roads and corrodes the undercarriage of cars and the embedded rebar in roads and bridges. The salts also eat away at residential plumbing and leach lead and other harmful minerals from public water distribution lines. Runoff from piles of rock salt remaining on the road after storms harm nearby waterways.

Now in the second year of study, The Watershed Institute and the New Jersey Watershed Watch Network work with about 100 community volunteers who help monitor and assess the salinity of freshwater streams in the winter throughout New Jersey. They share their results with state officials and contribute to a nationwide study, Winter Salt Watch, conducted by the Izaak Walton League of America.

Now in the second year of study, The Watershed Institute and the New Jersey Watershed Watch Network work with about 100 community volunteers who help monitor and assess the salinity of freshwater streams in the winter throughout New Jersey. They share their results with state officials and contribute to a nationwide study, Winter Salt Watch, conducted by the Izaak Walton League of America.

“This study is vital for freshwater scientists, municipal officials and others to gain a greater understanding of how to balance public safety with healthy waterways in New Jersey,” said Erin Stretz, Assistant Director of Science & Stewardship at the Watershed, who also is the coordinator of the New Jersey Watershed Watch Network.

“By collecting this data, we hope to communicate the depth of the damage that road salt inflicts on our freshwaters to those who maintain the roads,” Stretz added. “It is crucial to protect public safety for winter travel, but we can do this better.”

That ongoing study has found that roughly 20 percent of sample results exceed the New Jersey water quality standards for salinity of 230 mg/L, roughly equal to ⅓ cup of salt in an average bathtub. Of 115 streams and lakes monitored so far by our volunteers, 24 have surpassed the state standards. Locally, these include the Millstone River in Plainsboro/Princeton Junction, Swan Creek in Lambertville, Lewis Brook in Pennington, Spring Lake at Roebling Memorial Park and Dam Site 21, both in Hamilton.

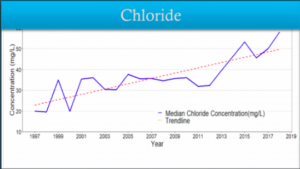

Cumulatively, the impact of road salts applied in winters over the years has resulted in significantly elevated salt levels in many of New Jersey’s waterways, according to the state Department of Environmental Protection. In fact, the median chloride concentration in New Jersey has tripled since 1997.

Long after winter has ended, the effects of road salts linger. Chloride continues to be released into our water from deposits stored in sediments, groundwater, and surrounding soils. At moderate chloride levels, fish, amphibians, and macroinvertebrates have a slower rate of growth and reproduction, and overall diversity is reduced. At higher concentrations, chloride can be lethal to freshwater organisms.

Alternatives to rock salt exist, but state officials say they also have drawbacks. Some products with organic material, such as sugar, may have an unintended side effect of reducing dissolved oxygen in water bodies. While sand does improve traction, it does not melt snow and ice. And, all too often, the sand washes into streams and ends up smothering aquatic life.

A combination of further monitoring, scientific studies, and shared best management practices – such as allowing more salt on gradients and curves while applying less on flat straightaways – is needed to inform state and local policies and regulations. The goals are for municipalities, businesses, and residents to cut back on waste, reduce road salt usage to appropriate levels, and avoid over application.