For the second straight summer, Rosedale Lake in Mercer County has been hit by harmful algal blooms (HABs) caused by the excessive growth of small organisms that produce toxins in the water — posing perils for public health and safety.

For the second straight summer, Rosedale Lake in Mercer County has been hit by harmful algal blooms (HABs) caused by the excessive growth of small organisms that produce toxins in the water — posing perils for public health and safety.

These toxic algae blooms are most commonly caused by phytoplankton known as cyanobacteria that use sunlight to create food. A combination of hot weather, nutrients from fertilizers, pet waste and other sources create conditions where cyanobacteria to grow too rapidly, producing toxins that are harmful to people and pets.

Environmentalists are concerned that these toxic algae blooms will become a chronic problem without better controls on the use of lawn fertilizers, farm run-off, septic leaks, polluted stormwater runoff and other contaminants flowing into the waterways.

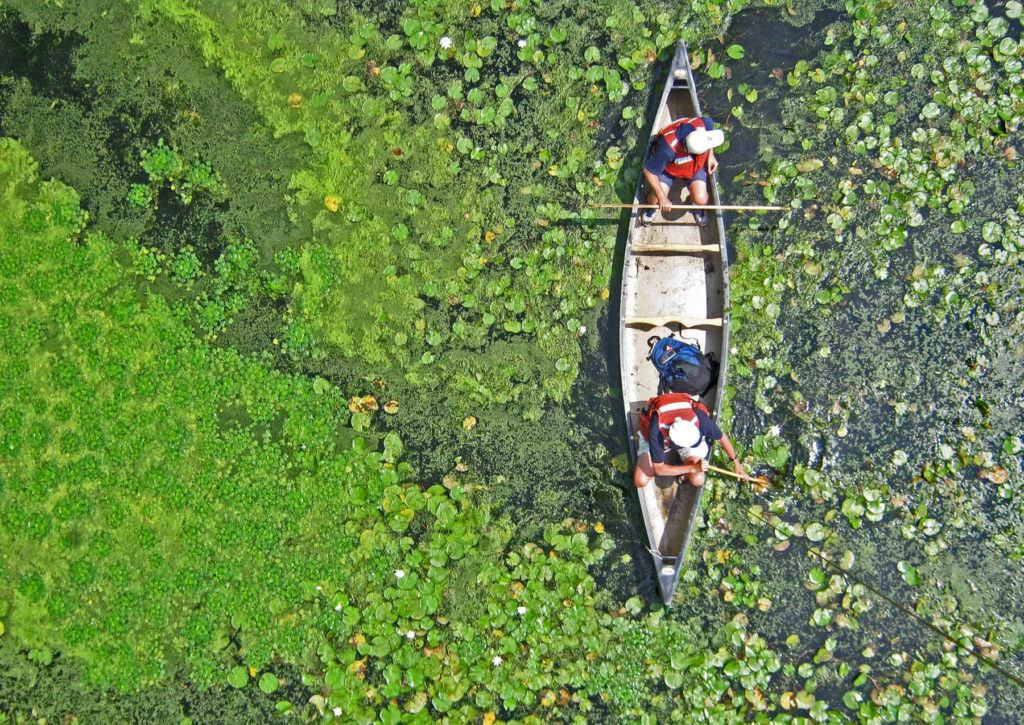

People and animals may be exposed to these harmful toxins when they swim, wade, boat or play in contaminated water, eat tainted shellfish or consume HABs-laden drinking water. People can be harmed by skin contact, ingestion or inhalation, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

With summer 2020 just underway, the state Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) already has identified two lakes in New Jersey with HABs: Rosedale Lake in Mercer County and Mountain Lake in Warren County. Dozens of lakes were closed last summer to swimming, fishing, and other recreation, including Rosedale Lake and Lake Hopatcong, the state’s largest freshwater body, which straddles Sussex and Morris counties.

The Watershed Institute is assisting Mercer County officials with possible remedies at the 32-acre Rosedale Lake. Funded by a $185,000 NJDEP grant, the Watershed and county officials over the next 26 months will implement and gather data on solutions such as floating wetlands, installation of an aeration device, and the use of barley bales to filter stormwater runoff.

The Watershed Institute is assisting Mercer County officials with possible remedies at the 32-acre Rosedale Lake. Funded by a $185,000 NJDEP grant, the Watershed and county officials over the next 26 months will implement and gather data on solutions such as floating wetlands, installation of an aeration device, and the use of barley bales to filter stormwater runoff.

“We’ve had success in installing floating wetlands to absorb excess nutrients,” said Steve Tuorto, Director of Science & Stewardship at the Watershed. “We’re hopeful this will be a non-intrusive and effective solution.”

The floating wetlands, installed successfully at an East Windsor retirement community, are planted with iris, willows and other vegetation with long roots. The plants and soil medium soak up the nutrients and help mitigate the algae blooms.

While New Jersey alone can’t halt rising global temperatures that fuels the bloom growth, environmentalists say the state can take steps to reduce the polluted stormwater runoff that carries bloom-inducing contaminants.

Additional use of green infrastructure, such as rain gardens and vegetative culverts, are needed on the local level to correct years of poor stormwater management by towns and to help halt the flow of contaminants into waterways.

An ongoing green infrastructure project in Hopewell Borough demonstrates how rain gardens and bioswales mimic nature by using plants and soil to absorb, cleanse, and slow down stormwater runoff before it flows into Beden Brook.

The Watershed Institute has advocated for the creation of local and county utilities to manage stormwater and fund projects like those underway in Hopewell. Last year, the New Jersey legislature authorized such stormwater utilities to address polluted runoff and the problems that ensue from it. The Watershed is also working with municipalities to strengthen their local stormwater ordinances in order to prevent new developments and redevelopments from exacerbating the problem.

While years of effort most likely are needed to rid New Jersey’s waterways of harmful algal blooms, homeowners and farmers may help out by changing habits to reduce nutrient pollution of our waterways from fertilizers, pet waste and poorly maintained septic systems.

NJDEP has a new interactive mapping tool that shows the location of HABs and ranks them with a color-coding system by the severity.